A new call for papers has been published for articles relating to the development of different types of hubs as part of rural and regional development strategies. Full details are available on the Local Economy website: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/lec and can be downloaded here: hubs and rural and regional development

Is it too late to save the rural economy?

It is very clear that the government’s lockdown policies are no longer about protecting the NHS which has ample capacity and is now failing people in many other ways as a result of the fear instilled by the handling of the Covid-19 crisis. On those grounds, one might question why lockdown rules remain in place at all.

However, my argument here concerns a lack of rural proofing of the government’s actions. The latest delays on re-opening parts of the leisure sector and the communication of new restrictions across Lancashire and Yorkshire suggest that no consideration has been given to distinctive rural issues nor to the urban-rural variation in rates of spread or risks to human health. Data from Centre for Towns identifying the rapidly escalating job losses and fears about the future of our graduates are surely more alarming? https://www.centrefortowns.org/blog/51-weekly-bulletin-on-covid-related-job-losses-14th-july

The last-minute reversal of plans to allow closely managed access to sporting events has been devastating for their respective industries, just as the quarantine rule changes have for the international travel sector. The knock on effects have seen other smaller events cancelled simply through fear. They may sound small and trivial but ceramics fairs such as the one in Southwell http://www.ceramicsinsouthwell.org.uk/ , whose cancellation was announced this weekend, are vital for networking, connecting with customers and orienting the work of a number of very small producers whose businesses may now fail. Some agricultural shows have attempted to operate online but these have been unable to recreate the retailing opportunities that are so important for many rural craft businesses.

In business, we all know that uncertainty is the biggest obstacle to firms getting back on track. Sudden decisions informed by the science of small numbers and with insufficient attention to regional difference must be challenged on grounds of being disproportionate and failing to weigh up multiple socio-economic impacts. As restrictions eased, businesses invested in ways to reopen safely so they must be given the chance to earn back that investment with the confidence that if they stick to the rules, they can make plans for the future.

There is, perhaps, just time to save tens of thousands of jobs by easing lockdown measures and maintaining the support and cooperation of businesses who are working so hard to keep trading AND to keep people safe. If these business go to the wall, BOTH the economy and the safety measures employed by businesses will be lost and the result will see poorer-managed and less safe activities taking place across the country – whether that is 1,000s of anonymous people packed on trains to the coast, as we saw last weekend, or growing civil unrest in the face of economic hardship and social breakdown.

I urge the government, and everyone who wants to help our young people, to take action before it is too late.

Time to reopen village playgrounds

While this post is clouded by personal views, it is also a reflection about how external (urban) views about rural places directly impacts our lives and communities.

Most of our town and city parks have remained opened throughout the Lockdown (albeit with play equipment and other facilities closed) to provide much needed space for exercise and the therapeutic benefit that green space provides. However, in smaller villages, there is often only a playground and their closure is increasingly detrimental to the social, physical and emotional detriment wellbeing of young children. I am not exaggerating – my son actually cries if we walk past it (so I try to avoid those routes) and he asks us every night when he can go to the playground again.

There is perhaps a mistaken assumption that all of the countryside is one big “playground”. From an urban perspective, this is quite understandable as their interaction with rural places is principally for recreation and the enjoyment of nature and the escape of the city environment. There are many areas around Britain that fulfil such roles but these equate to just a tiny proportion of rural England. It is quite sensible to leave the larger attractions closed for a little longer as they will pose a greater risk due to the scale of visitor numbers from a range of origins but this should not cloud the decision-making concerning smaller local attractions and village-based amenities that serve a relatively small number of people from a tightly-bounded area.

The sad irony for many villagers is that without playgrounds and sports-fields they do not have access to safe spaces for playing outdoors. I have been driving 5 miles to a nearby park to allow my son the freedom and space to run around, something that he cannot do along a country lane, farm track or in our small garden. I believe this is within the rules but with our village playground reopened, it would be unnecessary. For those adhering strictly to the “no non-essential travel” rules, they have been able to take advantage of the quieter village roads and heightened awareness of drivers that have resulted from lockdown. As Britain gets back to work, many of these exercise routes will become more dangerous and very young children will not be afforded the same freedom to cycle or run along our village paths. A lot of the most remote rural villages have very few pavements and while the landscape is aesthetically appealing, it is of course not open access to all.

Therefore, on the grounds on urban-rural equality and for children living in rural areas without million-pound mansions and the equivalent garden, duck ponds and swimming pools enjoyed by a tiny elite, PLEASE RE-OPEN OUR LOCAL PLAYGROUNDS.

Slightly more detail on the regional impacts of Covid-19

ONS data has revealed that total deaths in England and Wales in week 14 this year (week ending 3rd April) were 16,387, an increase of 6,082 on the 5 year average of 10,305. This was the first occasion that the average death toll in England and Wales has exceeded the 5 year average since mid-January. The ONS reports that these are heavily concentrates in London, with hotspots in the North-West and West Midlands too.

Nationally, the number of deaths attributed to Covid-19 in the week ending 3rd April was 3,475. This raises a serious concern about the causes of the additional 2,607 deaths.

A total of 2,367 deaths during the reporting week were attributed to influenza and pneumonia which could be undiagnosed Covid-19 but this figure is only 303 higher that the equivalent 5-year average for similarly deaths (2,064) so this is not the answer. How do we explain the 2,000+ additional deaths?

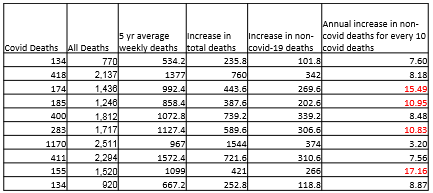

Breaking this down to the regional scale, using my own calculations of average weekly death rates from the past 5 years of data provided by ONS gives the following comparable death rates for the week 14, which was the first full week of lockdown in the UK, ending on 3rd April 2020:

The right hand column compared the increase in non-Covid-19 deaths with the increase in Covid-19 deaths. Where it is coloured red, this indicates that a greater increase in deaths resulting from FACTORS OTHER THAN COVID-19 than from Covid-19 itself. In two regions, for every 10 deaths resulting from Covid-19, we are seeing more than 15 additional lives lost which would not be lost in a normal year.

At this stage, the assumption is that people who did not die of Covid-19 are in the “Non-Covid” category. This is where we need to introduce Government Statistics of people dying who tested positive with the virus but for whom it was not their registered cause of death.

In the same week, government data for deaths associated with Covid-19, a broader measure, returned higher toll by a total of 470 losses of life. If we reduce the non-Covid death rate in line with this so as not to mis-attribute these case, an adjusted set of figures is shown below.

|

Region |

Covid Deaths |

Increase in non-covid19 deaths compared to 5yr averages (adjusted) |

Increase in non-covid deaths for every 10 covid deaths |

|

North East |

134 |

83.62 |

6.24 |

|

North West |

418 |

280.91 |

6.72 |

|

Yorkshire & Humber |

174 |

221.44 |

12.73 |

|

East Midlands |

185 |

166.41 |

9.00 |

|

West Midlands |

400 |

278.61 |

6.97 |

|

East |

283 |

251.83 |

8.90 |

|

London |

1170 |

307.19 |

2.63 |

|

South East |

411 |

255.12 |

6.21 |

|

South West |

155 |

218.49 |

14.10 |

|

Wales |

134 |

97.58 |

7.28 |

We have to recognise that the government dataset has faced additional criticism for missing deaths at home and in care homes so this too is expected to overstate the proportion of non-Covid deaths. Nevertheless the important point that there are strong regional variations, which we would expect to be greater at more localised scales, adding weight to calls for a regional relaxation of lockdown to save lives. As more detailed information is provided from ONS, we urgently need to identify whether the additional deaths are unreported Covid-19 consequences or other consequences of the state imposed lockdown.

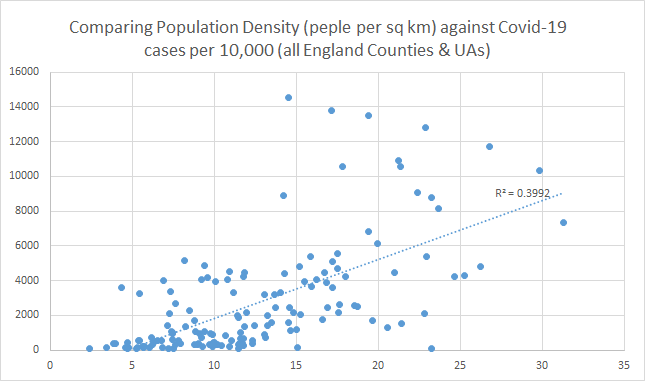

Coronavirus thrives in densely populated regions

It has been claimed on twitter that England will have one of the highest death rates from Covid-19 because it is one of the most densely populated countries. This isn’t just a case of “more people = more deaths” but represents the fact that people living, working and travelling around in close proximity is a major cause of accelerated transmission. Worse still, it appears, where people are exposed to multiple doses of the virus, they suffer more severely.

Based on this premise, I carried out a small piece of analysis to look at the regional case across England. While the data needs some tidying to remove the greater weighting afforded to urban districts in it’s present form, I still wanted to share this graph as it strongly suggests that we could consider alleviating lockdown earlier in more sparsely populated areas – just as long as we authorities remain alert to the risk of new clusters as in the Cumbria case. More updates to follow…