A new call for papers has been published for articles relating to the development of different types of hubs as part of rural and regional development strategies. Full details are available on the Local Economy website: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/lec and can be downloaded here: hubs and rural and regional development

Category: Uncategorized

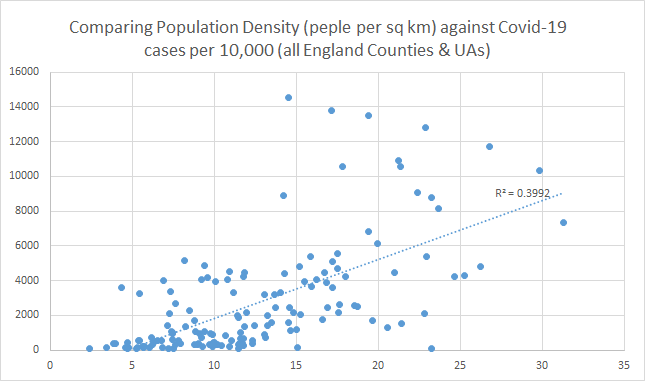

Coronavirus thrives in densely populated regions

It has been claimed on twitter that England will have one of the highest death rates from Covid-19 because it is one of the most densely populated countries. This isn’t just a case of “more people = more deaths” but represents the fact that people living, working and travelling around in close proximity is a major cause of accelerated transmission. Worse still, it appears, where people are exposed to multiple doses of the virus, they suffer more severely.

Based on this premise, I carried out a small piece of analysis to look at the regional case across England. While the data needs some tidying to remove the greater weighting afforded to urban districts in it’s present form, I still wanted to share this graph as it strongly suggests that we could consider alleviating lockdown earlier in more sparsely populated areas – just as long as we authorities remain alert to the risk of new clusters as in the Cumbria case. More updates to follow…

Designing research for Impact: The Regional Studies Association (RSA) Early Career Conference, University of Lincoln, 2019.

Lincoln School of Geography and Lincoln International Business School hosted the RSA’s Annual Early Career Conference on 31st Oct – 1st Nov 2019. It was with bated breath that we anticipated the opportunity to examine the overnight impacts of a “no-deal Brexit” but, for better or worse, that was not to be!

This was one of the first conferences to test the “carbon choice offer” being pioneered by the RSA where 8 presenters joined via video-conference. These included speakers from Germany, South Africa and Portugal and Chile.

The “best paper award” went to Rossella Moscarelli from the Politecnico di Milano in Italy for her innovative work on slow tourism as an opportunity to regenerate marginal areas. This was particularly fitting as the topic truly crosses over research in fields of business and geography.

It was particularly interesting to see how PhD and early career researchers are already having significant impact through a number of channels. We saw delegates working with diverse stakeholders including planning professionals in Nigeria, health services in England and regional development agencies in Lithuania.

The take-home message for PhD students as they look for their first post-doctoral academic position was that, while publication is essential, so too is networking and recognising multiple audiences for their research. In a world of “fake news”, we must all strive to promote the value of robust research evidence.

New social mobility report

The latest “State of the Nation” report from the Social Mobility Commission presents a much less detailed geographical analysis of regional differences in social mobility. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/social-mobility-in-great-britain-state-of-the-nation-2018-to-2019

The accompanying press release set out a much stronger emphasis on “class privileges” when compared against the 2017 report which drew our attention to challenges of poor social mobility in more rural regions, and notably here in the East Midlands.

One wonders why the spatial variability has now been relegated to 4 pages towards the end of the report (123-127) when the urgent need for spatial rebalancing of the UK economy and society remains a key issue.

Rural Research Methods

In the second meeting of Rural Visions, we discussed some of the distinct challenges and opportunities for carrying out research in rural contexts. Gary Bosworth (School of Geography) began by discussing the value of mixed methods to capture a full understanding of rural issues. Despite funding calls promoting mixed methods, there has been only limited progress in the number of publications in the main rural journals using mixed methods. It was argued that this could relate to word-count limitations, prejudices within journals or the inevitable problems that arise from multiple reviewers favouring either qualitative or quantitative methods.

Mixed methods can help to overcome some of the limitations of secondary datasets, which often only give the “bigger picture” perspective and lack the quantity of data when compared to urban regions. It was noted that smaller numbers in rural areas also give rise to ethical considerations and confidentiality concerns.

A further advantage of mixed methods approaches is that researchers can overcome problems of different definitions and representations of rurality. Combining statistical and policy-based delineation of rural places (more likely applied in quantitative data) with alternative socio-cultural interpretations of rurality (requiring a more qualitative lens) can draw out the true influences that rurality may have on the issues being studies.

The second presentation, from Fen Kipley (School of Social and Political Sciences), drew on her personal experiences of community-based research in former military housing estates in rural Lincolnshire. Fen emphasises the extra need to engage with ALL members of the community in order to gain their trust. In a rural setting, the researcher quickly becomes known to the community and attending all sorts of events is an important way to be seen as impartial. In Fen’s case this included sessions with the pre-school, with pensioners, with parish councillors and other voluntary associations and even going to church. Combined with the distances that can be involved and poor transport infrastructure and often limited places to stay, this all adds to the time required to gather robust qualitative data in rural areas.

Building trust with residents empowered people to engage in workshops and speak passionately and positively about how they could improve their communities. Fen’s use of “Appreciative Inquiry”, borrowed from business research, proved particularly effective at overcoming stigma attached to certain aspects of the local community too. As well as trust-building, immersion in the local community is also critical for understanding the internal power relations and identifying (and maybe circumventing) gatekeepers to give a voice to all people in rural communities.

In summary, we concluded that rural research is not just distinguished by small numbers and practical challenges of remoteness. Researchers must also be attuned to local community dynamics and avoid making assumptions about what the rural means to people living and working there. Entering the rural territory with an open mind and a willingness to listen, understand and give voice to residents will deliver the most meaningful insights… but this takes time and commitment.